By Will Barber Taylor

The world is very different today to the world that existed in the 1930s and 1940s. It is in many respects unrecognisable – a world that is, by all means still divided and to an extent racked by prejudice but one that is not as riven as that of generations past.

Yet, there are many things that can be learnt from that period. If the late 1890s and early 1900s represent the birth of the Labour Party and the 1910s and 1920s represent its development, the 1930s and 1940s represent its renewal.

Prior to 1945, Labour had only led the British government for a handful of years and had been only represented in one other government, that being the Coalition Government that occurred during the First World War.

Whilst it is often remarked upon that Labour has spent more of its history out of power than in it, most of the time it was in power occurred after 1945. Without the period of renewal in the 1930s and 1940s the Labour Party may not still exist today, and British politics and society would be the poorer for it.

To analyse what is behind this renewal, this article will look back at some of the literature produced during this period. By looking back at the material and understanding the context in which it was written, it will become apparent the degree to which the Labour Party was able to reassert and repurpose itself in the 1930s and 1940s and why this period is so critical for understanding how Labour was able to cement itself as one of the two dominant parties in modern British politics.

The 1910s and 1920s saw the Labour Party grow and develop. From a party that had fewer than fifty seats at the beginning of the 1910s to by the end of the 1920s having close to 300 seats and being in government for the second time in that decade, Labour made extraordinary leaps and bounds which would have certainly astonished many of the party’s earliest adherents.

Yet, in many ways, the 1929 result turned out to be a pyrrhic victory for Labour soon found itself dealing with one of the most disastrous economic downturns that has or will ever likely be seen in modern economics. Ramsay MacDonald’s decision to enter into a government of convenience with the Conservatives and some Liberal MPs because his own party would not back spending cuts, ironically did not end well for Labour. MacDonald, the man who was responsible for ensuring Labour made significant gains in 1906 was the man who ensured it made significant loses in 1931.

It would therefore have, for many commentators, seemed likely that after the 1931 election the Labour Party would have ceased to be. Yet the 1930s and 1940s in fact proved to be a period of great intellectual debate and indeed the breeding ground for Labour’s triumphant return to govern in 1945. This article will therefore focus on publications from prior to 1945.

The two main areas that literature from this period falls into are works dealing with the economy and those dealing with the oncoming storm of the Second World War. To begin with, let’s look at the pieces written focussing on Britain’s economy:

Labour and Britain’s economy in the 1930s and 40s:

The Labour Party’s great defeat in 1931, as mentioned above, was a fundamental shock to the system of the party. It had through the 1920s made rapid progress and advanced from a party on the fringe to one of government. For that to seemingly be taken from it was a stark and dramatic blow to the moral and psychological ability of the party to argue that it could govern again after such a defeat.

The 1931 defeat was recorded in detail by John Strachey in his book “The Coming Struggle for Power.” Strachey quoted Herbert Morrison as saying in the wake of the defeat “Socialism in our time is all romanticism.” Morrison’s colleague Stafford Cripps argued that “Gradualism is gone from the Labour programme forever” and Arthur Greenwood, future leader of the Party said “I know the Communists are always saying that the Labour Party supresses the militancy of the working class. This is completely untrue; the working class in this country is not militant and if it were, the Labour Party would welcome it.” The wake of 1931 had shattered the expectations and beliefs of many members of the Labour movement and to come to terms with this shock, some decided that Labour had to be bolder whilst others suggested that the party needed to dispel the myths about itself and take a more cautious approach. This set a pattern of internal analysis that has been replicated every time the party has suffered a heavy defeat with the solution often resulting in a compromise between the two positions.

Yet, it is clear that the economic shock of the 1929 crash and the poverty that continued throughout the 1930s gave Labour’s writers and many of those forming the party’s policy hope that the gradualism that they described could eventually give way to a more ambitious programme for government.

This boldness can be seen in the work of writers like John Strachey. Strachey’s work focussed on the evils of capitalism in relation to the poverty that he saw around him. Strachey’s trajectory as a politician is similar to that of many other Labour figures of the period – a Labour MP until the party’s defeat in 1931, Strachey became more sympathetic towards communism until he saw the actions of the Soviets during the early years of the Second World War. Like Denis Healey would go on to recount many years later, there were many young Labour figures who were enthusiastic about communism until they saw the consequences of it and Hitler and Stalin’s Non-Aggression Pact. It is perhaps understandable why the likes of Strachey would turn to the communist cause, in reaction to the betrayal as they saw it of their movement by Ramsay MacDonald. For Strachey, the depravation that was encountered by him and other Labour writers was as a result of “the recurrent crises of capitalism”.

For Strachey, the only way to solve the ills of modern society was to produce a plan to solve it. That “capitalist production is carried out without plan” meant the need for bolder solutions to tackle societal injustice. For Strachey it would be measures that took inspirated from John Maynard Keynes – the lack of regulation of the economy meant that it was easy for the continual crisis of capitalism to continue unabated. To our eyes, the kind of regulation suggested was hardly incessantly radical; for example, the regulation of bank institutions and a focus on using central banks to set and control interest rates.

At the time, however, the idea of contrasting or in some controlling the market was seen as tantamount to economic blasphemy. For Conservatives, regulation equalled a stifling of the movement of free trade. Even those who in the Conservative movement of the past had attempted to implement regulation, such as the Corn Laws or Joseph Chamberlain’s Tariffs campaign had done so with the desire to protect their own economic interests rather than to use regulation as a means of improving standards or stabilizing the economy as Strachey and other Labour thinkers of the time wanted to.

Later in 1933 and initially published in the Daily Herald, H V Morton’s essay on the state of the slums in Britain would shock many for how graphic it was and what it revealed about the state of society; that for all the great reforms of the early twentieth century under the Liberal governments and even some work enacted under Labour and Conservative administrations, the scale of slum living in Britain had not truly changed since the dark days of the Victorian era. The satanic mills, rendered so famously by Dickens and his contemporaries were still alive and well in Britain.

Morton begins his essay by explaining that “In this year 1933, when men can sail the Atlantic and speak to the ends of the Earth, millions of men, women and children are living in conditions callously decreed for them in 1833 – a peak period in the history of the world’s greed. Every city reproduces these conditions. They are called slums.”

For Morton the sheer incessant depravity of the slums was not simply shocking it was an insult, as he put it in the title to the first part of his essay to “Religion, Science and Progress”. How was it, Morton wondered, that with the great advances that had been made with technology it was that “Lovely, clean children” were born into what he said “are nearer to hell than anything Dante imagined.” For Morton, it was not just that the slums were bad for the health or that they represented and economic failure of an unconstructed capitalist system but that they also “warp the mind.”

Morton meant by this that the slums created a lack of inspiration, that the crime that was often associated with slum dwellings was not only a result of desperation, but also because of the sheer depravation of circumstances that surrounded those who lived in them. Morton remarked that the hovels he saw in Birmingham, Staffordshire and throughout England were only fit for firewood and that he wondered how “in an age of scientific discoveries” it was possible for so many people to “exist domestically in the surroundings of a dark, dreadful and backward period in history.” One young man Morton met in Liverpool remarked that the first fifteen years of life were the worst because if you lived at least fifteen years, “you go on living.” The sheer depravation, the lack of basic essentials and the cramped conditions of the back to back tenement housing horrified him as it did so many others.

Yet, despite the clear evidence that action needed to be taken to make the lives of the poorest better, the shock of the 1929 Wall Street Crash resulted in a reluctance, both from the governing Conservative Party and even some at the heart of the Labour Party, to hold back on advocating for anything that might seem fiscally responsible.

This attitude towards so called fiscal responsibility and the need to rebuke it would become more important to the Labour Party as time went on. It was this economic argument against Labour, that the party would somehow bankrupt the nation, that was used throughout the 1930s. It would still be used when Labour entered government in 1945. Whilst in government the notion of caution related to necessary financial expenditure was perhaps best dismissed by Michael Foot in his semi satirical work Brendan and Beverley:

“All this talk about balanced budgets is as dead as the dodo. The British Government hasn’t balanced its budget for years. Professor Keynes is against it. He’s been against it since 1929, and now, let me tell you, he’s a Governor of the Bank of England and a Baron into the bargain. As for President Roosevelt, he doesn’t know the meaning of the word, and he’s just going to be elected for another four years. I advise you therefore, Mr Tadpole, to forget about balanced budgets and never to mention the subject again.”

Whilst it was easy to mock the party’s detractors who would see any spending on welfare as potentially perilous to the economy as being concerned more with their own bank balances than with creating a wider welfare state for those who needed it, there was a very real and very tragic side to the firm austerity that was felt by many in the wake of the 1929 crash – the depths of poverty that many people felt across the nation.

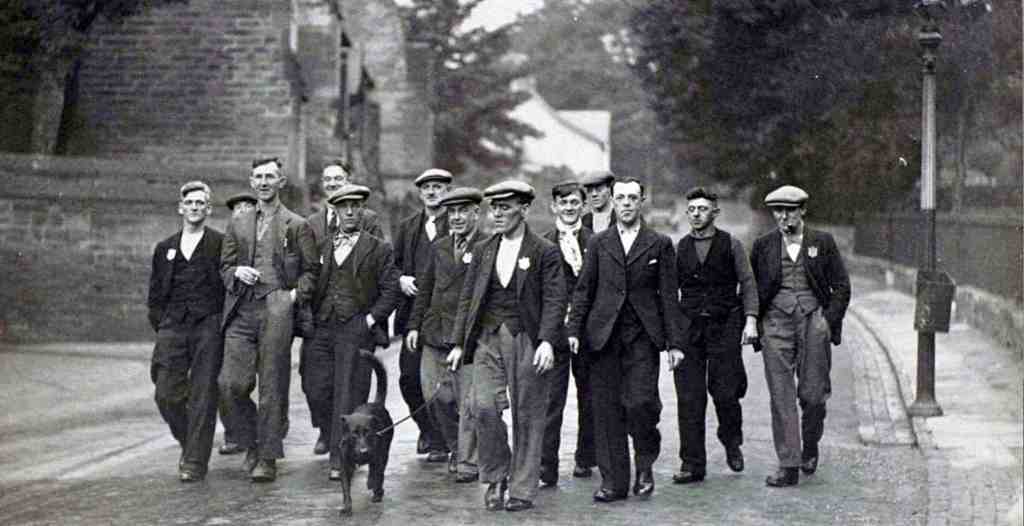

Wal Hannington’s 1937 book The Problem of The Distressed Areas built upon the type of literature that was already readily available to Labour authors at the time on the vast levels of poverty experienced throughout the country at the time, including H V Morton’s 1933 work on slum dwellings. Hannington’s book went further due to its length, explaining in frank detail the depravity that was being experienced across Britain at the time, combining his heart-rending descriptions with images making it abundantly clear the conditions that millions of Britons were living in, in post 29 crash Britain. Like Orwell’s Road to Wigan Pier, Hannington focuses on instances that he had witnessed in order to illustrate his point about the wider systemic failings of society and the government:

“One thing that will strike the observer in the wintertime in the Distressed Areas is the number of men who even on a cold day are to be seen without an overcoat. Take a look at a funeral procession in South Wales these days. The custom is for the relations and friends to walk behind the hearse to the cemetery, and the miners, who in times of good trade always had a preference for smart blue serge suits, would turn out in their best apparel and bowler hat, and present an exceedingly respectable appearance. But not so today. A funeral procession in the Rhondda Valley bears the marks of extreme poverty. The few serge suits which are seen can be marked out by their cut as pre war or immediate post war, because for years no new clothes have been bought.

People who were once too dignified to look at second hand clothing now scramble for it when it is sent into mining communities by patronizing organisations. I know of a particularly cheap brand of cigarette which, when introduced into the Distressed Areas, was eagerly taken up because of its cheapness. They were vile things to smoke and even those who smoked them would joke about their asphyxiating effects. But they went on smoking because they could afford nothing better.”

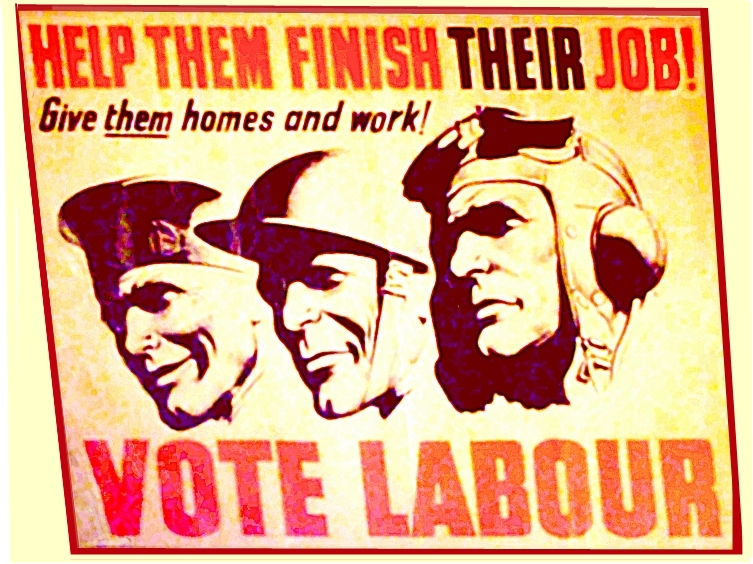

The kind of poverty that had been written about prior to Labour’s birth and which had motivated many of its early founders into becoming politically engaged in a new party had not dissipated. Whilst the reforms of the Liberal governments of Bannerman, Asquith and Lloyd George had certainly helped they had not gone far enough for many of those who made up the ranks of the Labour movement. It would be the combination of this wave of poverty with the further devastating impact of the Second World War which would ensure Labour’s landslide return to power in 1945. The popular view that Labour’s return was as a result of a desire to rebuild Britain because of the war is only partly correct; the burning injustice of inequality was passionately held by Labour writers and thinkers from the 1930s through to the 45 election. The war was simply the final straw for communities that had already been wrecked by years of falling living standards and a failure to feel a part of any kind of prosperous society.

It is because of this that many suggest, had MacDonald’s reaction to the Wall Street Crash followed the more economically redistributive ones of Roosevelt then he and Labour would have ultimately been more successful. This does misjudge the character of MacDonald; he was not a risk taker in the vein of Roosevelt. He certainly took risks such as his stance during the First World War and indeed his career standing for Labour when he could have as easily taken a Liberal seat (offers were made to Hardie and MacDonald at various points to take Liberal seats in order to kill Labour at birth – both naturally declined) could be viewed as risky. But he took risks only when he had to. MacDonald was a pragmatist and understood that politics required trade-offs. For him, his deal with the Liberals in the 1900s was the same as his deal with the Conservatives in the 1930s – a compromise in order to ensure a better Britain. That his latter decision was ultimately the wrong one is easy to say in hindsight, but at a time when the methods being enacted in America to stimulate the economy were both new and controversial, MacDonald’s hesitancy was understandable if not forgivable. The man who had helped set up the Labour Party in its early years in part due to his own inaction, would help focus it even more strongly on the economic injustices that faced millions of Britons.

The need for constructive change and to put as much distance as possible between the current party and the seeming failure of MacDonald by arguing for that change is key to understanding the thought process of the time and how Labour reinvented itself during this period. G D H Cole argued in A Plan For Democratic Britain that “the Labour Party believes that the primary function of government is to promote the welfare of the people, and that it is an essential duty of the Government to ensure that all the essential resources of the community shall be applied to promoting this end.”

For Cole, its wasn’t simply a case of entirely changing the system of educational support and governance, rather he argued that “one of the main tasks of the Labour Party, early in its period of office, will be not so much to devise new services as to bring those which are already in being up to standard. The State has already accepted the obligation to do something towards the prevention of distress and the creation of decent conditions for the whole people in childhood and adolescence, in manhood and old age. Where this something falls short of what is needed, it will be the mission of the Labour Party speedily to enact that the State shall undertake something more.”

For Cole as much as for Gaitskell there was a hesitancy as to how far the Labour Party could or should go in its economic and social redistribution. The devastation of the war would provide the reason – that it had depleted the nation to such an extent that greater boldness was not only needed but necessary – for policies like the creation of a National Health Service and the nationalisation of major industries to be accepted not just in Labour, but outside it as well. Labour, though often in later years smeared as being a party of mass revolution, was particularly potent for members of the public in the early 1930s in the wake of the Zinoviev Letter and Labour’s own former Chancellor decrying the party at the 1931 election as being “Bolshevism run mad.”

It was for this reason that Cole, Gaitskell and others would make clear the hatred of poverty whilst also shying away from some of the more radical solutions suggested by their fellow Labour thinkers. It is why, when dealing with the inequalities that govern education, Cole is quick to reinforce that Labour believed in free education for all but that the ultimate goal of free education for all would have to be “translated into action only in stages.” The caution would of course be overridden by Labour’s eventual election victory – though there are those on the left who today would suggest that Labour’s programme in 1945 was still a cautious one.

The inevitable anger at the National Government and later Conservative governments failure to deal with the economic fall out of the 1929 crash in the way many in the Labour Party wanted inevitably caused it to be the main issue for the party for the first few years of the 1930s and would heavily inform both the 1935 and the 1945 election campaigns. Yet ultimately, as the storm clouds gathered over Europe and the dark stain of fascism began to bleed across the continent, writers and activists began to turn to another important subject; that of war.

Labour and the looming war

As Mary Agnes Hamilton argued in The Labour Party Today, that by 1935 “it was plain much lost ground had been recovered and the fallacy of the “indispensable leader”” had been dismissed. The party’s confidence which had been so shattered by 1931 election had been restored by 1935 in part due to the steady stewardship of Deputy Leader and eventual leader Clement Attlee, but also thanks to the bustling wave of ideas that were flooding into the party.

Yet following the 1933 election of Adolf Hitler in Germany and as the decade progressed, greater and greater need was felt by those at the heart of the party’s leadership to emphasise the importance of defence and Britain regaining ground in terms of its military prowess.

Mary Agnes Hamilton goes into great depth to provide an official rational for how Labour gained its policy of rearmament:

“Labour strove, from 1918 on, for justice and fair treatment for Republican Germany. After 1933 it accepted the necessity of rearmament and pressed that it be accompanied by large scale measures for national control over the supply services. It bears no responsibility for the hideous failure in elementary duty which the Chamberlain government was to cite, in September 1938, as excuse for the shameful betrayal of Czechoslovakia. Labour would, in conjunction with other peace loving and democratic powers, have defended Austria in March 1938 and Czechoslovakia in September; and it is entitled to claim that resistance then, might have called a halt to the ruthless advance of Germany and prevented the danger that now threatens this and every other free land.”

Whilst Hamilton’s account is coherent and certainly the one that the leadership would have liked to have been seen by the public, it is not entirely accurate as to the degree of agreement that existed in Labour over the issue of war and rearmament.

Yet rearmament was not merely a moral position – it was also a political one. With the Conservatives dominating British politics for so long in the run up to the Second World War, the war itself, the rise of Hitler and Britain’s woeful military capability could easily be blamed on Labour’s main rivals. Robert Fraser, for example, blamed the failure of the League of Nations in part on the lack of a Labour government in Britain at the time of the rise of fascism: “when in 1931 the League had to face the first big test of its capacity to ensure justice and to keep the peace it was already flabby. It looked big and imposing, but the muscle was not all it might be. It was, however, by no means dead. The British Labour Government had done much to improve its strength and standing in the world. But when the test came, the Labour government had fallen, and the National Coalition had been formed.”

Fraser was not alone in his vocal criticism of the Conservatism and his argument that had Labour been in power during the years preceding the war it would not have occurred, or Britain would have been more readily prepared. For R Palme Dutt in his book examining then recent politics, World Politics 1918 – 1936, the weakness of Britain in standing against Germany’s building military might in the run up to the war was simple – “the policies of imperialist Governments can never be a substitute for independent struggle of the masses of the peoples themselves in all countries for peace and against the policies of their governments driving to war.” That more had not been done to fight against “the most savage and decadent class dictatorship of reaction known to history” was for Dutt and many other Labour members an indictment of not only the government but of British society.

The rumbling and impending background of war dominated the public conscience during the 1930s just as much as the economic situation did. The extent to which it fixated people can be seen from the introduction to Frank Tilsley’s book We Live and Learn in which he says “At thirty five I am half way through my allotted three score and ten years: whether I live through the other half of them is by no means certain. Rarely have people had so precarious a hold on life as we have who are living today. The knowledge that we are living on the edge of a precipice forms a background to our minds from which we cannot altogether escape.” The precipice was one which motivated the Labour movement to desire a better world once the threat of Nazi Germany had been dealt with.

As the war progressed, Britain’s victory in it was seen not simply as an opportunity for the Labour Party, who had gained in confidence since effectively ensuring that Winston Churchill became Prime Minister, but as Harold Laski argued for a potential revolution across Europe. In the first essay for a Fabian Society book designed to explore what Britain would need after the war ended, Laski outlines that it was not simply Britain which would benefit but as he saw it, all of Europe:

“The destruction of Mussolini and Hitler is essential to the salvation of Europe. But we shall not understand this war if we attribute its coming solely to the malevolence of these evil men. This war is merely the second act in a vast world drama on which the curtain went up on 4 August 1914. It is in part a struggle for world domination between old empires and news; in that sense those are right that speak of it as an “imperialist war”. It is also the declaration of bankruptcy on the part of capitalist civilisation. It is the proof that the operation of the profit-making motive can no longer produce either a just or peaceful society.”

Whilst many on most sides of the political argument would have agreed that only by defeating Hitler and Mussolini could Europe be saved and nor could many doubt that the causes of the Second World War were linked in some part to the end of the First, Laski’s insistence that the war proved the “bankruptcy” of capitalist civilisation was not one that would generate much appeal with either the public or the entirety of his own party. Certainly there was a drive to, as Laski suggested to “reorganize the foundations of our society” and deal with the “cash nexus” but it was not one that would spell the total and instant end of capitalism in Britain.

Indeed, in his book Money and Everyday Life, Hugh Gaitskell writing just before the war began sets out a view of a transitional economy, stressing that

“The British Labour Movement only in the use of democratic methods to achieve its aims. This makes even more inevitable the existence of a “transition period”. Socialism cannot be introduced overnight. There must therefore be a time during which Labour holds power without the economy of the country being socialist.”

The internal battle within the party as to whether the war should be seen as a moment to throw off all the shackles of the old world and embrace a socialist utopia, or whether a slow and steady transfer was one that had existed prior to the Second World War, but the war itself only intensified the debate. This is perhaps best reflected in the way this period has been considered historically and both Chris Clarke and Steven Fielding have written extensively on how modern historiography, particularly that promoted by left wing groups and figures, see the Attlee government of 45 – 51 as both a golden age to be striven for again and one that whilst making progress did not push far enough given the context of the time.

That the war could provide a means for pushing further and for truly and markedly changing Britain is seen throughout the collection Laski introduces. Harold Nicholson, an early critic of fascism suggests the creation of a “New World Order” in remarkably troubling terms (Nicholson refers to using the “material advantages of Hitlerian system plus the spiritual advantages of liberty and self-respect” and suggests that some of the criticisms provided by Hitler and Mussolini of democracy had” much truth” to them. Like Laski, Nicholson viewed the war as an opportunity – an opportunity in his case to advocate for a world government that would somehow free people from, as he saw it, the shackles of artificial creations like countries. Nicholson’s idea of a world order seems shocking given the precise nature of Nazi Germany’s aims in 1941 when he wrote them and certainly Nicholson may not have fully appreciated how his words would be viewed in the future. The nature of change that is advocated for all those featured in the collection is undoubtable however – it is change that is fundamentally radical and unapologetically so.

Indeed, Ellen Wilkinson’s essay that is near the end of the book equally judged the need for changing arguing that “the vast economic equalities are senseless. From every point of view they are utterly indefensible and utterly bad.” For Wilkinson as for most other Labour writers and thinkers of the time the war and its devastation was both tragic and a potential opportunity for change:

“As I go round bombed London, and as my work takes me to every nook and corner where houses and factories have been levelled and some of the loveliest of ancient things have been broken, I don’t get any heartrending feeling about that, because if we can keep the people alright, if we can get the people through and if we can give the children a chance, then out of the bricks and mortar, out of the very rubble of destroyed buildings, we can build something infinitely lovelier than the best of what we have lost. It would not take long to build something very much better than the worst.”

It was this fundamental desire, as clearly expressed in the literature of Labour Party writers during this period, to build a new Jerusalem, to take the ideas and activism of the 1930s and 1940s and force itself into something productive rather than merely being romantic rhetoric. Labour’s purpose has always been to turn discussion into directives for a new direction of political and social travel for Britain and it is no better illustrated than in Michael Foot and Donald Bruce’s Who Are The Patriots? Written in 1949 with an election on the horizon, already Foot and Bruce were using a certain nostalgic glow to paint the 1945 victory in:

“Do you recall the days of July, 1945? It is worth glancing back for a moment. A mood of relief and expectancy filled the air. The great German armies had been thrashed and a prodigious attack on Japan had been prepared. After six weary years during which the British people had endured and surmounted every trial and during which they had fought longer than any other great nation except the defeated Germans themselves, they naturally desired some easement from their hardships. But they knew also that tough problems lay ahead, and they were determined to rebuild after the fighting in a way very different from that which had been attempted after the First World War. In that spirit, they elected a Labour government to power.”

What the literature of the 1930s and 1940s Labour Party teaches us

The literature examined in this piece is only a fraction of the total sum of all the work produced by Labour Party writers, members, and activists during the two dramatic decades of the 1930s and 1940s. The ideas that were being discussed were various as well and it would be wrong to lump all the literature into the two groups of concern about the economy and the looming war in Europe. A great deal, not addressed in this article, was produced dealing with the subject of Empire and of the organisation of the state.

Yet what the literature that has been looked at demonstrates is that the 1930s and 1940s represented a turning point for the Labour Party, one in which it utilised the failures of the incumbent Conservative government as a means of creating a programme ready to fix the nation once Labour returned to office in 1945.

It was not of course simply a case of the literature of the time representing some great plan to take the Conservative’s worst failures and throw them back at them – they also represent a frank expression of the issues that mattered the most to the British people. The depravation of the 1930s and the fear of total calamity from war both before and during the conflict battered the public’s sense of faith in government, a faith that was restored with Labour’s election in 1945. The literature that came before it laid the foundations for the ideal of a new Jerusalem that the Labour Party of 1945 would seek to build amongst the ruins wrought by victory.

They discussed and argued why greater intervention was needed in the state and the economy and they set out how Britain could and should have dealt with Nazi Germany, although perhaps much of what was written owed something to hindsight. The literature of Labour’s second birth is crucial to understanding the party’s appeal after the war and how the Attlee government was able to enact such change so quickly. A nation that had been deserted of aid and leadership for so long found it in the Labour Party. Although the 1945 government was not successful in all it sought to do, the seeds of its success can be found by looking at the rich and illuminative literature that came before, literature that articulated the collective desire for change better than any single speech ever could have done.

It is perhaps fitting to end on a note of comparison between the literature produced here and that produced in the run up to the 1997 election, the election that this website is dedicated to analysing. Whilst there are many differences between the run up to the 1997 election and the 1945 election, not least that in the run up to 97 Labour had already had two transformative periods in office whilst prior to 1945 Labour’s time in government was brief, there are some similarities. The writing of both times demonstrates a wealth of ideas and a desire to implement them. Whilst it would be wrong to exactly compare Britain in the 80s and 90s to that of the 30s and 40s, the desire for change was paramount in both eras and at the heart of the intellectual debate occurring in Labour. Similarly, the focus on both the economy and Britain’s place in the world were key to Labour’s success in both elections – not just pointing out the failure of the Conservatives but providing solutions to those failures. In both instances the feelings of a grinding failure of progress, of the utter dismay at the never-ending stream of examples of the country failing to work were core to the Labour Party’s success both in 1945 and 1997. The literature of both eras reflect that and it is only through reading that literature and understanding the emotions that drove the authors to put their words to the page that we can fully comprehend why the Labour Party returned to power in 1945