By Will Barber Taylor

It is a moment that has become crystalised in the memory of those who were both there and those who heard it since – Neil Kinnock, standing in front of the assembled ranks of the 1985 Labour Party Conference and uttering the words “A council, a Labour council”.[1]

It is a phrase that has gained a life of its own. The reason for this is not only its part in one of the most famous speeches in the history of the Labour Party, one which saw Kinnock take on Militant but also because of the emphasis that was placed on Liverpool City Council being a Labour council and therefore one that should have been held to a higher standard than one governed by another party.

For if there is any political party which owes its roots to local government, it is not the Liberal Democrats or the Conservatives, despite their representation on such elected bodies – it is the Labour Party. For both from its very earliest day in the mists of the late 19th century to today the Labour Party has always been the party of local government.

The Seeds of a Revolution: Labour Councillors During The Early Years

To stress how much the Labour Party’s history is intertwined with that of local government we only have to look back at the very first Labour councillors – councillors who proclaimed they were Labour even before the party was formally founded.

Whilst 1900 is regarded as the birth year of the Labour Party by some, the party’s foundation is much muddier than might be thought. 1900 marks the year in which the Labour Representative Committee, the precursor to the modern Labour Party, was founded. Of the two Labour MPs that were elected, only Keir Hardie could be said to be truly a new kind of MP.

Richard Bell, a native of Hardie’s new constituency[2] and the other MP elected for Labour in the constituency of Derby would eventually be thrown out of the Labour Party for failing to adhere to its rules;[3] some historical comparisons might be drawn between Mr Bell and a subsequent MP for Derby but they aren’t for me to comment upon.

Even in 1906, another year that is often considered to be the foundation year for the Labour Party, Labour was not truly the party it is today – you couldn’t be a member of the same party that was elected to sit in Parliament; you could be an affiliate member of the ILP which was the closest thing to representing the membership but party members and MPs would not be truly united under one roof until the 1920s.

Regardless of the party’s origins however, the signs of the future were present much further back than the turn of the century. Whilst as far back as the 1860s and 1870s there were MPs and councillors who were referred to as “Liberal – Labour” this marked them out solely as being further to the left of the traditional Liberal Party in supporting trade unions; they were still at their core Liberals.

However, by the 1880s this would change. Thanks in part to the popularity of a variety of new political traditions that were entering British life (Georgism, the Land League movement, Marxism, temperance, suffragism (both male and female) and the beginnings of domestic anti imperialism) the feeling that the Liberal Party would not give the people what it wanted began to burgeon into the desire for a party of “Labour.” Greater opportunities would arise for working class representation on a local level thanks to the creation, between 1888 and 1894 of new county and urban district councils and the abolition of the cumulative property vote in Poor Law Guardian elections.[4]

This move for greater opportunity in local government for those who saw themselves outside the Liberal/Tory divide coincided with the foundation of the Independent Labour Party in 1893 in Bradford. Whilst there had been Labour organisations before, the ILP was the first party that seemed at least to combine the various new politically different strands into one party. It would soon make small but significant gains in various local authorities. The architect of the ILP’s local elections domination was Philip Snowden, the future first Labour Chancellor of the Exchequer. Snowden had begun his conversion to left wing politics thanks to the plight of growing up in rural, impoverished Yorkshire.[5] After a bicycle accident ended his career as a civil servant with the Inland Revenue Snowden returned to Yorkshire, determined to make a difference.[6]

Rather than setting his sights on Parliament, Snowden set them on local government. Soon he and other Yorkshire based ILP firebrands like Herbert Horner[7] and James Teale[8] were making waves in school board and parish council elections. Snowden soon earned himself as reputation as “a sharp thorn in the side of the Liberals”[9]. It may seem remarkable today but the Labour Party’s first tentative steps towards power occurred not in gaining industrial seats on Parliament but gaining seats on local boards and parish councils in rural areas like Cowling, where Snowden grew up. This was partly because of a dissatisfaction with the party of Gladstone and partly due to the individuals who stood for Labour. In rural areas in which personality mattered, the personalities of Snowden and his colleagues would often help shift votes one way or the other.

The gains on school boards as particularly interesting because they demonstrate that there was a desire for change to those that governed local children’s educational services. In the days before national curriculums and education for all, who was on the local school board made the difference between a child having a good education or one which was marred by uncaring and unimaginative educators. More significant changes came in 1894 when women gained the right to vote in some rural, parish and urban elections.[10] Whilst it would take until 1918 until women over thirty with certain property rights could vote in a general election[11] and universal suffrage would not be achieved until 1928[12] at a local level in some elections women gained this right decades earlier. The change in the right to vote meant women who had been campaigning in the Labour Party for years could finally represent it on a local level, the most well known being Isabella Ford who was elected in 1895 to Adel Cum Eccup parish council and would remain the Labour Party’s only elected woman councillor until the turn of the 20th century.[13] Ford was remarkable in her campaigning against animal cruelty, in favour of universal women’s suffrage and in favour of finding a peaceful end to the First World War. She would also become the first woman to speak at a Labour Representation Committee conference and become one of the first women to be on the committee of the Leeds Arts Club.

This was not simply limited to the rural north; however, one of the ILP’s most stunning victories was to briefly gain control of West Ham council in 1898[14] though this had as much to do with the influence of its former MP Keir Hardie as it did on the appeal of Labour to local constituents.

Despite the importance of these gains, they were ultimately not enough to save the ILP. After Labour failed to gain any seats in the 1895 UK General Election, and only gained two in the 1900 General Election it became clear that the current structure of the party was not fit for use on a Parliamentary level. This was in stark contrast to Labour’s regional success. In 1903, Labour won control of Woolwich Council[15] and in 1904 Fred Jowett made Bradford Council the first council in Britain to assume responsibility for children’s school food, providing free school meals for all.[16]

On a regional level Labour was already making a difference – however, this wasn’t the case on the national level. In part this was because that it was easier, given the less competitive nature of parish guardian elections for example, for Labour to win over voters to them. Similarly, the sheer amount of council seats available meant the party could easily work with other small parties to get things done. For example, in the North of England, ILP councillors were able to work with SDF colleagues[17] whilst in London they banded together with Liberals on county councils.[18] The strength of the Liberals however meant that there was a risk that Labour could easily be swallowed into the larger party.

Because the trade unions and the Liberals had a grip of loyalty on many voters, it became apparent that Labour had to either make a deal with both groups or it would become extinct at a Parliamentary level.

The trade unions had been for, opposed to and at time ambivalent of the ILP seeing it as another fad party without much influence or at times a threat to the Liberals continuing dominance of centre left politics. Many ILP voters were accused of being splitters who would allow the Conservatives to win seats.

The Liberals were more fearful of the ILP’s ability to win seats off the Conservatives. Ramsay MacDonald, Labour’s future first Prime Minister was instrumental in mitigating both factors. He made a pact with then Liberal Chief Whip Herbert Gladstone that Labour and the Liberals would work together in some seats for the advantage of one another.[19]

MacDonald made similar progress with the trade unions by making them a core part of the newly established Labour Representative Committee, giving them the bulk of delegates of the various founding constituent parts of the Committee. Whilst the ILP would continue to exist for a number of years, both as the membership body of Labour and later as a splinter left wing party, it would never have the same importance as it did during its early years in power.

With 29 MPs in 1906, Labour had a national standing in Parliament which would have an influence on its success in local government. By 1913 Labour had gained over 200 councillors in the local elections at the borough, district and parish level[20] making the party a force to be reckoned with. Whilst the First World War split the party’s membership and MPs, the lack of homes fit for heroes as promised by Lloyd George, only resulted in an acceleration of Labour gains at the local level. It is also striking to note that at the war’s end, twenty percent of London Labour’s borough councillors (numbering 150) were women with ten percent (ten women) representing their wards on Liverpool’s council.[21] In the 1919 local elections that followed the end of the war, Labour won an astonishing 938 seats in the London and regional metropolitan borough elections alone[22]. It was a foreshadow of what was to come.

The same year, Clement Attlee entered politics as the Mayor of Stepney; his role in local government reflects how much of an influence local government would have on shaping the careers of Labour’s titans.[23] At the same time as Attlee assumed the mayoralty, his great rival Herbert Morrison was elected a councillor on Hackney council before becoming Mayor a year later.[24]

Revolt, Rates and Redistribution – Labour Councils in the Inter War Years

The 1920s, a decade in which even prior to the Wall Street Crash the divide between the rich and poor was more apparent than ever would see Labour briefly gain a foothold in government. Whilst Labour’s time in office would in both instances be brief it would build upon the work done by the party in local government and bring it to a national level.

A demonstration of the distrust came in 1921 when a revolutionary move was made by the Labour councillors of Polar who decided not to raise the rates in the area due to the high degree of poverty. Led by future Labour Leader and the former Mayor of Polar, George Lansbury, the 29 Labour Councillors who made the decision would eventually face prison due to their stand.[25] One, Lansbury’s daughter in law the Suffragette Minnie Glassman would contract pneumonia in prison and eventually died after she was released.[26]

Despite being imprisoned and MacDonald’s reluctance to support Lansbury’s illegal action, the move gained widespread public support and gave birth to the term Poplarism to refer to instances when local government stood up to central government on behalf of the poor.

Thanks to the popular stand of those brave Labour councillor in November of 1921 the Local Authorities (Financial Provisions) Act 1921 was rushed through Parliament in order to equal the rates paid by local authorities regardless of whether their inhabitants were rich or poor, meaning that poor areas like Poplar would not suffer from disproportionate taxation. It was an example of Labour in local government forcing change at a national level.[27]

It would not be the only achievement made by a Labour council during the 1920s. In the 1920s as Labour gained greater control over councils there was an expansion of unionised work in the building sector in particular which offered a life line for those workers who wished to be members of unions and not face discrimination.

Yet national government also called. In 1924, Labour was able to form its first administration with Ramsay MacDonald as Prime Minister. It would be short lived due to a number of factors, including those relating to Britain’s relationship with Russia.[28] Yet whilst Labour was in power it passed one truly significant piece of legislation the Housing (Financial Provisions) Act 1924, also known as the Wheatley Act because it was spearheaded by former Red Clydeside Labour councillor and Minister for Health John Wheatley.[29] The act ensured that over half a million homes were built by local authorities with low rents specifically for workers who worked the hardest jobs possible. Though the subsidies that the Act provided for would be removed less than ten years later, its impact on local communities and the local authorities that governed them was profound and ensured housing for thousands who had previously been deprived of it. [30]

Yet despite this, Labour would be removed from power and not return until 1929. That administration was similarly short lived and thanks to the Wall Street Crash and a political divide between MacDonald and his colleagues, the 1930s would at times see Labour go backwards at a parliamentary level. The 1931 election would see Labour’s worst defeat and in 1935, despite a massive improvement on the wipe out of four years earlier Labour was still massively behind.

Whilst the 1930s would prove to be a decade in which the Labour Party’s role in national government was diminished, this was not the case for its role in local government. Throughout the decade the Labour Party grew in influence over local government. Many councils that remained governed by the party for decades would be initially won in the 1930s. The 1930s also saw the creation, thanks to the national party, of the first model standing orders that had to be utilised by Labour councils.[31]

This was partly due to “neighbourhood based politics”[32] of the era that placed emphasis on local representatives making decisions for their residents but it was also down to frustration; for the majority of the decade Labour was out of power nationally and so it only made sense for those active in the movement to place all their energy into controlling councils across the country.

Yet, it was not simply electoral success that was important to Labour’s influence on local government during the 1930s. Efforts were made in 1934 following Labour’s winning a majority control over London County Council to create comprehensive style schools (known then as multi bias schools) but the move was not approved.[33] Similar inventive ideas were applied in Wales where, rather than administrating the harsh benefits means test exactly as the government ordered, the Labour dominated councils in Merthyr and Monmouthshire ensured that far more recipients got their benefits – in 1932 35% of all applicants in then non Labour controlled Birmingham were refused benefits whilst in Merthyr the figure was 1%.[34]

However, the most significant success was the pioneering of Health Centres which provided not only advice but medical care for those who could not afford to get a doctor to see them. In areas in which disease, workplace injuries and lack of medical attention were rife the creation of council health centres by Labour councils in Bermondsey and Finsbury in 1936 and 1938[35] were revolutionary.

By having salaried General Practitioners who were paid by the council to see to the needs of the local sick, Labour’s councillors ensured that a far better standard of medical care was available to the poorest members of society. The council Health Centres were effectively proto-NHS centres and demonstrate the radical work being done by Labour in local government.

“Now we are the masters” Labour Councils During The Attlee Government

The Second World War devastated communities across Britain and in its aftermath was felt by many, not just in the lives of those they had lost but also in the devastation that was wrought across the nation’s infrastructure. Whilst it is easy to imagine that the 1945 election represented a phoenix rising from the ashes of war, the picture was far more complex. On a national level, the Attlee government had to deliver a sizeable message of change whilst also dealing with a country that had suffered from years of war.

Local government was of course key to Labour’s success on a national level. In the 1945 local elections the party gained a whopping 1,600 seats on both rural and metropolitan borough councils[36]. The stage was set for change on a grand scale. Attlee’s time as Mayor of Stepney and serving on the council meant that he had an understanding not only of how local government could operate but also what could be done to improve it. Attlee’s time as Mayor was an important one to him and helped form his political character and his abilities as an administrator.

This change had been brewing during the war. Thought had been given as to what Britain would look like after the war and what would be needed to ensure that the nation could recover. The Future of Local Government, produced in 1943 went as far as to say:

“Any change in Local Government structure must vest full authority in the elected representatives of the people. The democratic tradition in local government is very powerful, and nowhere more so than in the ranks of the Labour movement. It is not enough merely to affirm this principle. Efforts must be made to translate Labour’s ideas and ideals into a constructive system of government that will conform to the necessities of historical development.”[37]

When Labour came into office efforts would be made to put this ideal into practise. The great vision, needed especially with the roll out of a brand-new National Health Service, was for the country to be divided into regions which could function as a means of delivering services quicker, more effectively and with an eye on implementation for more people. The main idea, to turn local government into a two-tier system, was a bold one. The aim was to abolish county councils and replace them with regional councils. They would be the first tier which would deal with wider areas (it was envisioned that they would be around a million people) and the second tier. being made up of district or borough councils, would deal with more local matters.

It seemed a perfect way to simplify the system of local government whilst also allowing for residents to still be able to go to a local representative than rather simply have to deal with someone whose responsibilities stretched much further than their local area. However, these bold attempts at reform were never passed simply because there was too much disagreement and too much for the Attlee government to do in its short time in office. Despite the clear signpost to reform set out by the Local Government Boundary Commission and others, reform did not occur.

Had the Attlee government enacted its reform of local government in the 1940s, the system would be not only far simpler now but may have proved to be more effective. It may be a failure, but it is one that was as ambitious and forward thinking as any of the 1945 government’s efforts.

Local government reform would dominate the discussion around regional governance for the next few decades. Yet, those who were involved in making decisions were unlike some members of Attlee’s government experienced in local affairs.

Reform, Reform and more Reform – Attempts to change Local Government from the 50s to the 70s

The 1950s would, like the 1930s, be a decade in which Labour was confined to the wilderness on a national level. Attempts were made to carry out more reform to local government along the lines of that proposed by Labour in the 1940s. The 1950s would see efforts to bring in reform via the Local Government Act 1958 which established a commission to look into local government in both England and Wales. The efforts of the act would be negligible because both commissions were abolished before they could fully report.

Labour returned to government in 1964 on a wave of necessary change after the crumbling of a Conservative government under a wave of incompetence and sleaze (sound familiar?). Harold Wilson, unlike his predecessor had been radicalised not by being a local politician but rather being a civil servant. Despite this, changes to local government would occur whilst he was Labour leader.

The London Government Act 1963, passed a year before his election, created the authority of Greater London and with-it Greater London Council which was established in 1965.[38] The GLC would be remembered most for its demise under Margaret Thatcher but during the 1960s it was more noticeable for its advocation of the London Ringways, designed to ease congestion in the capital but which would have resulted in the flattening of 300,000 homes.[39]

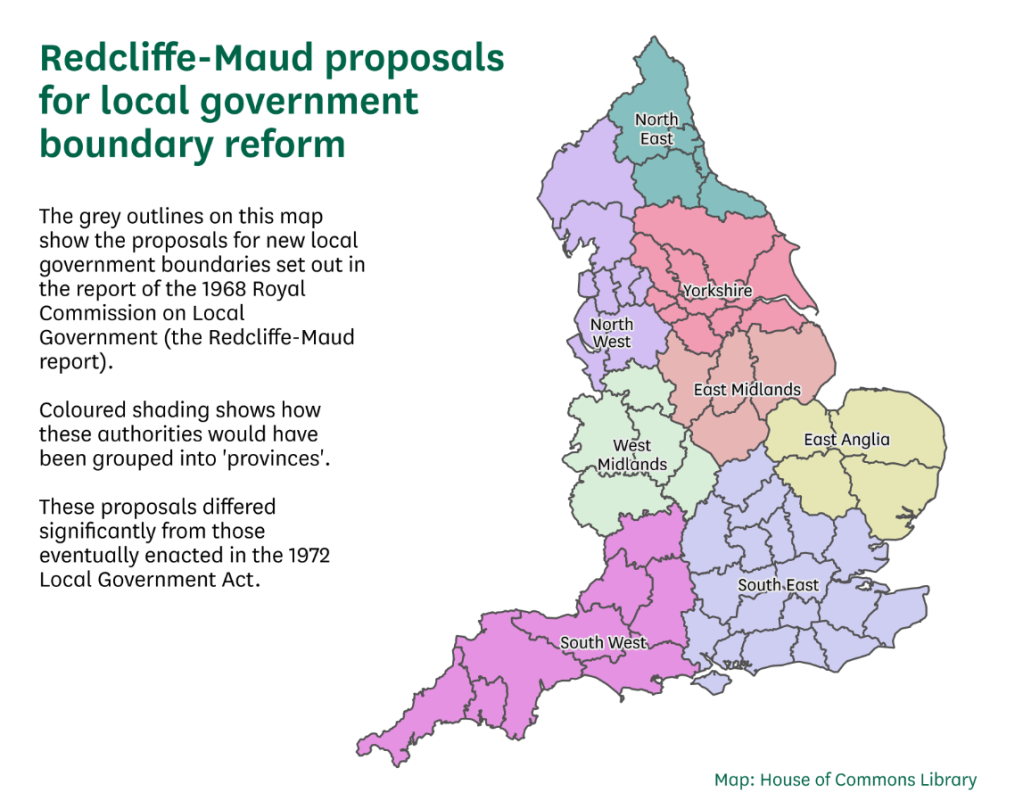

The 1960s would further see attempts by Harold Wilson’s government to change local government and make it less complex though unlike the previous attempts by the Attlee government to create a two tier system, the Redcliffe Maud report advocated for the creation of a single tier of local government. This was never carried out due to Labour’s loss in 1970.

Yet, whilst varying tinkering reforms were occurring on a national level, at a local level progress was still being made. Ambitious social housing projects were being enacted across the North by councils, like Hunslet Grange in Leeds which was envisioned as an ideal of future home ownership. Sadly, many of these efforts were mismanaged – although prefabricated industrialized homes were seen as a scientific and effective way to solve the housing crisis they did not live up to the dream.

The 1970s would in many ways prove to be similar to the 60s – many great ideas that were either not implemented or were not successful. The 1972 Local Government Act sought a further reorganisation of local affairs but only served to complicate matters further.

In 1974 Harold Wilson was returned to government and decided that in order to help fix the economic black hole that Britain was in, cuts would be need to public expenditure. Local councils would take the brunt of these cuts. Yet, whilst Labour continued in office, its local representatives began to diverge from the party. Whilst councillors had often been to the right of the Labour Parliamentary Party, due to losses of senior figures in council elections in the late 1960s and early 1970s they were replaced with young, community-based activists like John Gunnell who was a Labour councillor for Hunslet in Leeds and helped found the Hunslet Grange Tenants Association in 1978 in order to force the council to deal with the complaints of residents. [40]

By the end of the decade and the end of the Labour government of Jim Callaghan, Labour council workers and indeed some Labour councillors would be in open revolt against the government’s fiscal policies. The disconnect between “Sunny Jim” and Labour’s local representatives would be palpable. Much would be made in the coming decades by the Conservative Party and the Conservative Press of “Loony Leftie” councillors in order to demonise the work of Labour local authorities; however, like the 1930s the 1980s would prove to be a period of sustained and inventive policies for Labour councils which helped to improve the lives of people across Britain.

A local renaissance – Labour Council Successes in the era of Thatcher

In 1981, after years of campaigning, the WLM (Women’s Liberation Movement) achieved one of their aims – the creation of a Women’s Unit on Greater London Council.[41] The unit, the first of its kind in the country and by far the largest, would go on to help thousands of women across the city, by pushing for gender equality through a training scheme, discussing with women what they needed locally and used what feedback they received from women to push for policies that would help them.

Despite reluctance from a Labour party that both locally and nationally was still very male dominated, the GLC proved to be a template that would be copied across 47 local authorities by 1987 including Wolverhampton, Aberdeen, York and Bristol.[42] The hard work and determination of Hilary Wainwright, Jan Parker and Sheila Rowbotham[43] amongst many others was critical to ensuring that a much needed and highly effective part of local government was brought into being.

This was not the only radical change implemented by Labour councils during this period. In Sheffield, cheap bus fares were championed despite threats of legal action from the government. Indeed, it is stark the difference in bus fares in Sheffield as compared to other major cities. In 1985 an adult to buy a bus ticket for 10p to go anywhere within a six-mile radius of the city; in Manchester the fare was 58p for an adult, 55p in London and 50p in Leeds.[44]

The fact that Sheffield Council was able to enact such a policy – although it was ultimately a short lived one – demonstrates the determination of Labour councils to provide services at an affordable rate and ensure transportation was open to all. That at one time the citizens of Sheffield could travel to the Peak District for 20p[45] is a demonstration of true and demonstrably positive local action that allowed nature to not be confined to the rich but open to everyone, as it should be.

Whilst many of the achievements of Labour councils during the 1980s were ultimately short lived thanks in no small part to Margaret Thatcher’s government, they were important because they demonstrated that local communities could gain a great deal by being represented by the Labour Party. Whilst Labour in local government in the 1980s has sadly been often mischaracterised as the time of the “Loony Left”, there were many endeavours that were far from loony and indeed far sighted in their recognition of the basic needs as communities.

Of course, not all Labour Party council action during this period would be complete without reference to the titanic struggle between the Militant controlled Liverpool City Council and its poster boy Derek Hatton and the national party lead by Neil Kinnock. Kinnock’s task to present the Labour Party as electable and in keeping with the priorities of the public was undermined by Hatton and the Militant group’s attempts to ignore the Conservative government of the time’s cuts to public expenditure by setting an illegal deficit budget in 1986. This followed a rent cap rebellion in 1985. Both actions landed Hatton and the council in sticky water with the government and would eventually see them forced from office and expelled from the Labour Party.

Despite how often Hatton is associated with local politics during the 1980s he was, ultimately, an outlier who was more interested in his own self promotion then finding any workable solutions to the problems that faced Liverpool and Britain during the 80s.

In retrospect is perhaps sad but unexpected that the renaissance in local government occurred when Labour was out of power nationally – as in the 1930s, efforts were pushed into making local government the bedrock of Labour power and imagination because it seemed that the party was far from government.

This of course would change in the late 1990s.

New Labour, New Local Government? Local Government and the Blairites

The election of Labour in 1997 was a watershed moment in British politics. Tony Blair, his Shadow Cabinet and the entire party achieved the seemingly impossible and ushered the Labour Party into a new period, its longest period in government.

One of New Labour’s greatest achievements was devolution, not only in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland but also regionally as well. The Local Government Act 2000 was a significant piece of legalisation not least because it created the role of directly elected Mayors for the first time, giving regions a powerful local voice. Yet the act was also significant because it revised the ethical framework that applied to local authorities as well as giving them powers to promote economic and societal well-being within their boundaries. It also set out the need for every local authority to produce their own publicly available constitution.

These measures were important steps forward in giving local authorities new decentralized power. However, New Labour did have issues with local authorities as Patrick Diamond sets out in his excellent book The British Labour Party In Opposition and Power 1979 – 2019. In it, Diamond argues that:

“Ministers believed there was little appetite for localism for an electorate that rejected postcode lotteries. If they gave away control to local councils, ministers would get the blame when things went wrong. The legacy of the 1980s and so called loony Left councils meant instinctive mistrust of local government.”[46]

It was an understandable mistrust given certain council’s association (namely Liverpool) with Labour’s defeats during the 1980s; Militants actions stained all local authority initiatives with the same brush. Yet it was a mistrust that was ultimately unfounded. Local authorities have always disagreed with governments, whether they be of their own party or not, and yet it is better to work with them than against them. It is ironic in an era of “levelling up” that the idea that localism was unappealing to the British electorate was considered a concrete political judgement. Indeed, as had been the case in the 1980s, there were still tensions between the new shiny Labour Party of Blair and Labour councillors to the extent that in 1996 Hackney Borough Council’s Labour group was disbanded to prevent it from becoming a “party within a party.”[47] The shadow of Militant loomed larger and given that local council representatives were, quite literally, the party’s most active representatives in local communities it was important that they were able to follow the party line.

The lack of engagement with local authorities is ironic as Diamond acknowledges for the fact that in local government, New Labour lived on most by ensuring the election of “a succession of modernising leaders who pragmatically governed in the image of Blair and Brown.”[48] This was despite the fact that by 2009, a year before Labour entered the electoral wildness it only had 4,400 councillors, a sharp decrease on the 10,900 Labour councillors who were in office in 1996, a year before the first New Labour landslide.[49]

Despite its best efforts, New Labour would not succeed in entirely changing the status quo. In 2010 Labour lost power. It has yet to regain it on a Parliamentary level.

Local Government – The Future and the Front Line of Labour Politics

The return to government of the Conservative Party in 2010 has not helped Labour in local government. Cuts to public expenditure have hurt the party’s ability to govern across the country and in subsequent elections Labour has lost control of seats and councils that were once held by the party almost unopposed for decades.

Labour has lost four general elections now and whilst current polling is promising, the future is not set in stone. Yet whether or not Labour is able to return to power in Westminster at the next election, Labour must continue to govern as effectively as possible in local communities.

The work done by Liverpool Council’s House for a Pound scheme[50] and Norwich council’s social housing projects[51] are evidence of exciting and engaging work being done by the Labour Party at a regional level.

Throughout its history, from the very murky early days of the 1880s to now the Labour Party has been a party of community. It has been a party that is based on the aspirations of working people across this diverse and wonderful nation. It truly is a party of local government and one which will only be able to win the next General Election if it takes the enthusiasm and ideas that lie at the heart of local Labour groups and channels them into the heart of its next campaign.

[1] Neil Kinnock, Labour Leader Speech, British Political Speech website, http://www.britishpoliticalspeech.org/speech-archive.htm?speech=191 [Last accessed 27/03/2022]

[2] A J Anthony Morris, C. P. Trevelyan 1870-1958: Portrait of a Radical, (United Kingdom: Blackstaff Press, 1977) p 58

[3] Paul Adelman, The Rise of the Labour Party 1880-1945, (United Kingdom: Routledge, 1996) p 33

[4] John Gyford, Local Politics in Britain, [London: Crook Helm Ltd, 1984], p 50

[5] Philip Snowden, An Autobiography: Volume 1, (London: Ivor, Nicholson and Watson, 1934), p 50

[6] Colin Cross, Philip Snowden, (Great Britain: Barrie and Rockliff, 1966), p 14

[7] David James, “Philip Snowden and The Keighley Independent Labour Party”, Philip Snowden: The First Labour Chancellor of the Exchequer, ed by Keith Laybourn and David James (Bradford: Bradford Libraries and Information Services, 1987) p 8

[8] Ibid

[9] “The Meanness of Toryism”, Keighley News, 15 June 1895, p 4

[10] Nan Sloane, The Women in the Room: Labour’s Forgotten History, () p 62

[11] Women Get The Vote, UK Parliament, < https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/electionsvoting/womenvote/overview/thevote/>, [Last accessed 23/05/2023]

[12] Women Get The Vote, UK Parliament, < https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/electionsvoting/womenvote/overview/thevote/>, [Last accessed 23/05/2023]

[13] Nan Sloane, The Women in the Room: Labour’s Forgotten History, () p 62

[14] John Gyford, Local Politics in Britain, [London: Crook Helm Ltd, 1984], p 50

[15] John Gyford, Local Politics in Britain, [London: Crook Helm Ltd, 1984], p 50

[16] Marsha Singh, “Fred Jowett”, Men Who Made Labour, ed by Alan Howarth and Dianne Hayter, [United Kingdom: Routledge, 2006] p 115

[17] Nan Sloane, The Women in the Room: Labour’s Forgotten History, (Great Britain: IB Taurus, 2018) p 63

[18] Nan Sloane, The Women in the Room: Labour’s Forgotten History, (Great Britain: IB Taurus, 2018) p 62

[19] Duncan Tanner, Political Change and the Labour Party 1900-1918, [United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2003], p 21

[20] John Gyford, Local Politics in Britain, [London: Crook Helm Ltd, 1984], p 50

[21] Krista Cowman, “Municipal Socialism and Municipal Feminism”, Rethinking Labour’s Past, ed Nathan Yeowell, [London: IB Tauris, 2022], p 128

[22] John Gyford, Local Politics in Britain, [London: Crook Helm Ltd, 1984], p 50

[23] Jerry Hardman Brookshire, Clement Attlee, (United Kindgom: Manchester University Press, 1995) p 46

[24] John Gyford, Local Politics in Britain, [London: Crook Helm Ltd, 1984], p 63

[25] John Davis, Waterloo Sunrise: London from the Sixties to Thatcher, (United States: Princeton University Press, 2022) p 233

[26] Janine Booth, Guilty and Proud of It! Poplar’s Rebel Councillors and Guardians, 1919-25, (United Kingdom: Merlin Press, 2009) p 88

[27] Local Authorities Financial Provisions Bill 1921, Hansard, < http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/lords/1921/nov/08/local-authorities-financial-provisions> [Last accessed 27/03/2022]

[28] Gill Bennett, The Zinoviev Letter: The Conspiracy that Never Dies, (United Kingdom: Open University Press, 2018) p 4

[29] Ernest Darwin Simon, The Anti-Slum Campaign, (England: Longman, Greens and Co, 1933) p 36

[30] Ibid

[31] Colin Copus, Party Politics and Local Government, (United Kingdom: Manchester University Press, 204) p 127

[32] Michael Savage, The dynamics of working-class politics : the Labour movement in Preston, 1880-1940, [Great Britain: University of Cambridge Press, 1987] p 211

[33] David Rubinstein and Brian Simon, The Evolution of the Comprehensive School: 1926-1972, (England: Taylor and Francis, 2013) p 45

[34] Chris Williams, “Labour and the Challenge of Local Government, 1919 – 1939”, The Labour Party in Wales 1900 – 2000, ed by Duncan Tanner, Chris Williams, Deian Hopkin [Great Britain: Dinefwr Press, 2001] p 156 – 7

[35] Justin De Syllas, Integrating Care: The Architecture of the Comprehensive Health Centre, [United Kingdom: Taylor and Francis, 2015] p 9

[36] John Gyford, Local Politics in Britain, [London: Crook Helm Ltd, 1984], p 51

[37] Samuel Leff, The Health of The People, [Great Britain: Camelot Press, 1950] p 280

[38] Gloria Clifton, “Members and Officers of the LLC 1889 – 1965”, Politics and the People of London: The London County Council 1889 – 1965, ed Andrew Saint, (London: Hambledon Press, 1989) p 26

[39] Douglas A Hart, Strategic Planning in London: The Rise and Fall of the Primary Road Network, (Great Britain: A Wheaton and Co, 1976) p 167

[40] David John Ellis, Pavement Politics: Community Action in Leeds, c. 1960-1990, (England: University of York, 2015) p 37

[41] Krista Cowman, “Municipal Socialism and Municipal Feminism”, Rethinking Labour’s Past, ed Nathan Yeowell, [London: IB Tauris, 2022], p 131

[42] Ibid, p 132

[43] Ibid

[44] Daisy Payling, “Linking up Labour: Place, Community and Buses in 1980s Sheffield”, Rethinking Labour’s Past, ed Nathan Yeowell, [London: IB Tauris, 2022], p. 165

[45] Ibid

[46] Patrick Diamond, The British Labour Party In Opposition and Power 1979 – 2019, [Oxford: Routledge, 2021] p 294

[47] Colin Copus, Party Politics and Local Government, (United Kingdom: Manchester University Press, 204) p 103

[48] Ibid, p 294 -5

[49] UK Election Statistics, 1918 – 2022, A Long Century of Elections, < https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7529/CBP-7529.pdf> [Last accessed 23/05/2023] p. 83

[50] Liam Thorp, “How to get a £1 council house and how long you might have to wait”, Liverpool Echo, 13 Nov 2017, < https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/how-1-council-house-how-13894447>, last accessed 27/03/2022

[51] Aaron Morby, “Labour pledges biggest social house building plan since 1960s”, Construction Enquirer, 2019, < https://www.constructionenquirer.com/2019/11/21/labour-pledges-biggest-social-house-building-plan-since-1960s/>, last accessed 27/03/2022